“Good Teachers” have “Good Asks”

When it comes right down to it, teaching is comprised of only two things—asking students to do things and trying to get them to do them. Or, as I say, teaching is “Ask & Get.” Think about it. We “ask” students to come to school, behave responsibly, and complete assignments, and then we try to “get” them to do so. The reality is: we “get” some students to do so and others we don’t. What causes some teachers to “get” more than others? One key factor is, “good teachers have good asks!”

Let’s explore what I mean by “good teachers have good asks.”

There are three basic “asks” that exist in schools—procedural, behavioral, and academic.

Procedural “asks” consist of behaviors such as lining up, being prepared with proper materials, tossing your lunch tray in the proper receptacle, and evacuating the building during a fire drill.

Behavioral “asks” include working cooperatively with others, not running in hallways, and otherwise behaving appropriately.

Academic “asks” involve asking students to answer questions, think independently, solve problems, and do homework. And, let’s not forget the vast array of assessments that we ask students to take.

While we “ask” students to engage in these tasks, the reality is that not all teachers “get” students to do them or do them well. Of course, there are many variables that go into “getting” students to engage in these tasks. However, when we look at the variables that educators can control, it is apparent to me that some teachers are much better at “getting” students to engage than others.

Let’s explore why.

The first variable is that some teachers have better “asks.” In observing teachers who “get “ students to engage, there appears to be three dimensions to their “asks”—affective, quantity and quality.

The Affective Dimension

Building Strong Relationships

Teachers who have good “asks” tend to have high affect and nearly always have strong relationships with their students. Students who perceive that their teacher “likes” them and is concerned about their learning tend to be more motivated to engage in the “asks” that occur in the classroom. These teachers are empathetic, caring and kind. They are aware of their students’ personal interests and diligently work to create a sense of belonging among all students. Students who feel this sense of emotional safety are more willing to engage in the risks that often come with learning.

I remember years ago as a principal inviting a young girl to serve on the interview committee for a group of teacher candidates. While the teachers and administrators on the committee were asking questions about assessments, data-driven decision-making and collaboration, I invited the girl to ask any question she wanted because there was a chance that this could be her teacher. The question was so profound, that whenever interviewing teacher candidates, I always asked her question: “Are you nice?”

It is important to note that effective teachers maintain their authoritative demeanor while being nice. Nice doesn’t translate into permissiveness.

What I have noticed over the years is that teachers who “ask” nicely are much more likely to “get” students to respond.

In my training sessions, I refer to the next two dimensions as the “Q and the Q” or the Quantity and the Quality.

The Quantity Dimension

Engaging ALL Students

The first Q refers to the number of students who, when “asked”, actually do the work. It is clear that more effective teachers simply “ask” more students to do the work while less effective teachers “ask” fewer students. This is most obvious when a teacher “asks” an academic question of the class and then proceeds to “ask” students to raise their hands to respond.

When students engage by raising their hands, we know that very often only a few elect to do so. Others—particularly lower achieving students—choose to sit passively while the teacher calls on those who volunteer to answer. Teachers who employ more advanced strategies such as the use of think time, random response systems (e.g. electronic selection programs, popsicle sticks), reciprocal teaching, and  cooperative learning strategies all tend to “ask” more—or all—students to respond which results in more “gets.” These are what I call the “Equal Opportunity Teachers” because they have the skills to provide equal opportunities for all students to be engaged.

cooperative learning strategies all tend to “ask” more—or all—students to respond which results in more “gets.” These are what I call the “Equal Opportunity Teachers” because they have the skills to provide equal opportunities for all students to be engaged.

Of course, engaging all students is challenging and requires advanced techniques; many of the strategies used by effective teachers simply “ask” many more students to do the work and “get” more students to do it.

The Quality Dimension

Constructing Complex Tasks

While displaying the appropriate affect and using strategies to engage all students are important, the quality of “asks” we demand of students is paramount. The quality of the “ask” refers specifically to the cognitive complexity or depth of knowledge of what we “ask” students to do. To prepare students for life in a complex world where students have to navigate complex and complicated situations (e.g., health insurance, interest rates, voting) as well as perform on various assessments throughout their school experiences, schools must “ask” students to do various levels of work, including an ample number of highly complex tasks.

Effective teachers consistently “ask” students to do work that is of a higher level of cognitive complexity while less effective teachers “ask” an overabundance of lower complexity questions. It is imperative that teachers understand and construct good “asks” that require students to meet the academic demands of the standards they teach. School leaders must closely monitor and provide feedback on the various types of “asks” that occur in their schools.

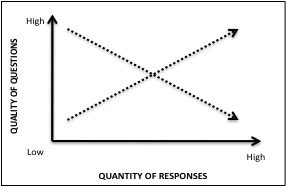

It is important to understand the relationship between the quality of the question and the quantity of students who respond. It is not uncommon for the quantity of students responding to increase when the quality of the question is lower. Conversely, when the cognitive complexity of the question increases, the quantity of students responding decreases.

Successful schools have spent significant professional development hours helping teachers and administrators understand the various levels of cognitive complexity and how that can be transferred to the activities that students are asked to do in the classroom. To master these skills it takes deliberate practice, quality coaching—including feedback—and time. As a result, teachers will have a deeper understanding of what quality student work looks like and administrators will be able to monitor and support teachers in “asking” students to engage in the work that will allow them to be successful in school and in life.

Summary

The most effective teachers have strong affect, are skilled at “asking” a variety of complex questions and can “get” large numbers of students to do high quality work. It is imperative that schools and school districts offer support and training to teachers and administrators in these three dimensions if they want their students to be successful.

Mark Rolewski has assisted schools and school districts in designing and implementing successful turnaround initiatives for over 19 years. Mark has assisted with school turnaround in many districts and schools including those in Florida, New York City, Hartford, New Orleans, Memphis, Kansas City and Los Angeles. He is widely sought after by schools and school districts to speak about and assist with turnaround initiatives. This is the sixth installment of an ongoing series that outlines many of the components of a turnaround initiative.

For additional information, please visit Mark’s webpage.

Click here if you would like to sign up to receive future articles via email. Thank you.