Making Teacher Growth Plans Relevant, not Compliant

At this time of year, teachers across America are designing and submitting for approval their Professional Growth Plans as part of the evaluation process. This annual ritual asks teachers to identify and develop a plan of action outlining an area of instructional growth. While this activity is well intentioned, it is my observation that these plans are largely ineffective, completed primarily to comply with state and district requirements, and—most importantly—they take away valuable time necessary to truly improve instruction in schools.

At this time of year, teachers across America are designing and submitting for approval their Professional Growth Plans as part of the evaluation process. This annual ritual asks teachers to identify and develop a plan of action outlining an area of instructional growth. While this activity is well intentioned, it is my observation that these plans are largely ineffective, completed primarily to comply with state and district requirements, and—most importantly—they take away valuable time necessary to truly improve instruction in schools.

Think about how this ritual typically unfolds. It begins with school administrators explaining to teachers the content, process, and format for developing such a plan according to district guidelines. Teachers, in turn write up their plan, submit it for approval and, if necessary, revise it based on administrative feedback. Once approved, teachers—due to their chaotic schedules—typically place their plan on a far back burner and continue their daily routine of planning, collaborating, teaching and completing the various other demands of the profession all the while trying to sustain some type of life outside of school. Come spr ing, teachers dust off their plans and begin the process of trying to document that they have completed their plan and frantically assemble the requisite documentation that will eventually lead to meeting the requirements of the plan. The results of the plans are submitted to the appropriate administrator who, in nearly all cases, provides the stamp of approval indicating that the requirements have been met.From an administrative standpoint, multiply this by the typically large number of teachers an administrator evaluates and you begin to understand the massive amount of time it takes to complete an activity that yields very little return on investment. Teachers and school leaders—especially in turnaround schools—have little time to engage in time-consuming activities that take away from true school improvement

ing, teachers dust off their plans and begin the process of trying to document that they have completed their plan and frantically assemble the requisite documentation that will eventually lead to meeting the requirements of the plan. The results of the plans are submitted to the appropriate administrator who, in nearly all cases, provides the stamp of approval indicating that the requirements have been met.From an administrative standpoint, multiply this by the typically large number of teachers an administrator evaluates and you begin to understand the massive amount of time it takes to complete an activity that yields very little return on investment. Teachers and school leaders—especially in turnaround schools—have little time to engage in time-consuming activities that take away from true school improvement

efforts. After participating in and observing this phenomenon for almost forty years as a teacher, principal, central office administrator and leadership consultant, I believe it is time to revisit this massive waste of teacher and administrator time. Here are my ideas. As always, I’d like to hear yours.

Timing

The first issue that needs addressing is the timing of when the plan must be designed and submitted for approval. In nearly all states where I have worked, this is around the month of October, which often coincides with the end of the first quarter. In my opinion, this is a terrible time for a teacher to identify an area of growth! Often our new teachers are already treading water as fast as they can trying to keep up with the behavioral and academic demands of the classroom, and we shout from the shore, “How about learning a new stroke?” Experienced teachers, too, are busy meeting the demands of student learning with little time to reflect on identifying a new technique. Don’t get me wrong. There are some teachers who handle this activity just fine. However, I think that with better timing we can significantly increase the return on investment of this activity.

I think a better time to identify and design a plan for developing a new instructional technique is in the spring, sometime after the final evaluation and before the end of the school year rush. Teachers—as all good teachers do—could spend part of their summer reading the educational research associated with their topic and thinking about how they will turn this newfound knowledge into a skill once the school year begins. Simply put, summer affords teachers the time to learn about the new technique and plan how they might integrate it into their teaching repertoire.

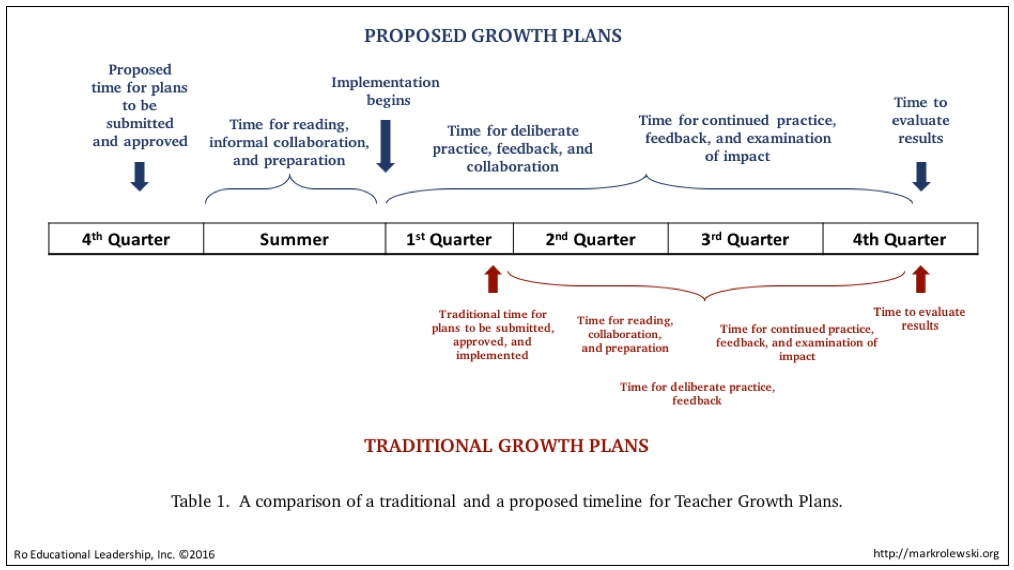

Plans that are implemented at the beginning of the year also benefit from the additional time—sometimes an entire quarter—that a teacher can practice a new skill. Imagine how much more skilled a teacher would be if they studied cooperative learning, for example, in detail over the summer and began implementing it the first day of school. Research has proven that time is important to learning something new, and maximizing the entire school year as opposed to starting after the first quarter just makes sense. (See Table 1)

Collaboration

I often present the groups I work with the following scenario:

“Two people join a gym. One joins alone and the other joins with a friend. In six months time, which person do you think will still be going to the gym to work out?”

Overwhelmingly, people select the person who joins the gym with another person as the one who will sustain their gym routine. When asked why, they always cite the benefits of being encouraged by and accountable to another person.

To me, the idea of each teacher identifying in isolation a new technique to learn and practice alone in the classroom without the benefit of a supportive colleague significantly decreases the probability of the plan being sustained. It’s no wonder why, as a part of my trainings, I ask teachers around November or December what they have selected for their focus area and very, very few are able to tell me.

The solution is to encourage teachers to develop their plans in collaboration with others—a colleague, a team or an entire faculty. In many states teacher autonomy to choose what they want to work on is critical. However, influencing teachers to work collaboratively does not violate the intent of this provision.

Feedback and Follow-Up

For one to become skilled in a new technique, it requires practice, feedback and time. However, teachers often practice new techniques by themselves in their classroom with little or no feedback. This type of practice tends to not result in very high quality as there is no frame of reference other than one’s self. Imagine what a great cook you would be if you were the only one to ever taste your cooking! It is not only important to become skillful; it is essential that we become skillful enough to affect student learning. This level of skill requires that we receive ongoing feedback and follow-up.

Furthermore, learning a new skill can be uncomfortable. Neurologically speaking, we are much more comfortable relying on the skills that have become habits as opposed to learning something new. Learning a new skill requires that we use the part of our brain that causes us to slow things down—or be deliberate—so our brain’s can learn the new behaviors. Over time, we learn to be less deliberate and more comfortable with our new skill. As we become more and more skilled we have to continue to receive feedback that will allow us to perform at an even higher level. Too often, after the first wave of discomfort is gone we think that we are now skilled. Understand that there is skill and then there is “skillful enough to impact student achievement.” Becoming highly skilled requires learning a skill and then being comfortable with the discomfort of learning it at a higher level. This cycle needs to be repeated in an ongoing manner to reach the level necessary to make a professional growth plan worth the effort.

Furthermore, learning a new skill can be uncomfortable. Neurologically speaking, we are much more comfortable relying on the skills that have become habits as opposed to learning something new. Learning a new skill requires that we use the part of our brain that causes us to slow things down—or be deliberate—so our brain’s can learn the new behaviors. Over time, we learn to be less deliberate and more comfortable with our new skill. As we become more and more skilled we have to continue to receive feedback that will allow us to perform at an even higher level. Too often, after the first wave of discomfort is gone we think that we are now skilled. Understand that there is skill and then there is “skillful enough to impact student achievement.” Becoming highly skilled requires learning a skill and then being comfortable with the discomfort of learning it at a higher level. This cycle needs to be repeated in an ongoing manner to reach the level necessary to make a professional growth plan worth the effort.

To remedy this, I believe that all professional development plans should include provisions for ongoing, actionable feedback that leads to high quality skill development. If we want to increase the rate of change, we must increase the rate of feedback. We also have to challenge the traditional thinking that feedback must come only from an administrator. Again, time is a significant variable and administrators simply do not have enough time to provide feedback to all the teachers that they are charged with supervising. Therefore, it is paramount that professional growth plans include provisions for peer feedback and time must be allocated for colleagues to serve as support to their fellow teachers. Without this, plans are pretty much worthless.

Observation of New Techniques

When working with teachers on new techniques, the overwhelming request I receive is that they want to be able to see it implemented in a high quality manner. Often, there are no models or exemplars to show them. Videos can help but tend to be less personal. When coaches can model the technique or when teachers can visit classrooms where their desired learning can be demonstrated, it adds tremendously to their understanding, particularly when they can talk with other teachers about the nuances of learning or implementing a new skill. Once a teacher has a picture in their head about what quality can look like with students, it adds significantly to their learning. All professional growth plans should include observation of the technique as part of the plan.

Tied to the Needs of the School

Often, teachers have the autonomy for selecting the technique that they wish to learn. While autonomy can contribute to motivation, for some reason this is not true as it relates to the professional growth plan since often compliance, not passion, continues to rule the day. While I am an advocate of teacher autonomy, I believe that schools—particularly turnaround schools—have comprehensive needs that will only be solved by dedicated people all pulling together in one direction on the techniques that will matter most. For example, I notice that a teacher might focus on homework as an area on which they want to improve their skills. While this might be appropriate for some schools, strengthening one’s technique in the use of homework does not have a significant effect size when compared to a technique such as cooperative learning or reciprocal teaching. Therefore, I recommend that in particular cases, school leaders should work with teachers to identify techniques that will have the largest impact on achievement in the school.

Impact on Learning

Finally, professional growth plans must not only focus on the process of learning a new skill but should also include provisions for its impact on learning. In working with teachers on developing new skills, we eventually reach the point when we start asking, “So what? Who cares if you have learned a new skill?” The ultimate question is “How did learning a new skill affect student learning?” I always encourage teachers to include measures of student learning so that they can see the impact and value of learning a new skill. There is a distinct difference between a teacher who returns to a session and is excited that they have implemented a new technique and a teacher who returns and shares student achievement data showing an increase in student learning. Remember, data are feedback and building student achievement measures into a plan guides it toward a higher level of implementation.

Summary

Administrators and teachers—particularly in turnaround schools—are busy people and have to be efficient and effective in their work. A nnual professional growth plans as outlined in most districts’ teacher evaluation process often have a large impact on time but little return on investment

nnual professional growth plans as outlined in most districts’ teacher evaluation process often have a large impact on time but little return on investment

in terms of strengthening instruction or increasing student achievement. It is imperative that we be thoughtful when implementing this requirement and do it in a manner that makes it both meaningful and impactful for all parties involved, especially our students.

Mark Rolewski has assisted schools and school districts in designing and implementing successful turnaround initiatives for over 19 years. Mark has assisted with school turnaround in many districts and schools including those in Florida, New York City, Hartford, New Orleans, Memphis, Kansas City and Los Angeles. He is widely sought after by schools and school districts to speak about and assist with turnaround initiatives. This is the eighth installment of an ongoing series that outlines many of the components of a turnaround initiative.

For additional information, please visit Mark’s webpage.

Click here if you would like to sign up to receive future articles via email. Thank you.

I appreciate your comments, Kathy. Lack of clarity is such a big issue in education. It promotes an unfortunate climate of confusion, compliance and apathy among teachers who generally want to meet the needs of the organization. Clarity only comes through clear communication that includes not only the “what” but the “why” and is grounded in dialogue to create a common understanding. The fact that you found clarity in your colleagues is a true testament to your professionalism.

Mark, so much of what you outlined in this article resonates with what I felt going through the process of designing and implementing my growth plans. In addition to trying to address the district goal, school goal, and a personal goal, it was difficult to keep clear what data I was collecting for what purpose and how it ultimately helped the growth of my students. Collaborating with other teachers in my subject or grade level helped me to clarify my thoughts and to see that we were having the same concerns and issues – always stronger working together~