Maintain Your Focus during the Holiday Run

The holiday season—Thanksgiving through the winter break—provides some unique challenges for school leaders. It is a time when school leaders are busy attending holiday concerts and plays, organizing food and gift drives for needy families, while still responsible for the normal (normal?) day-to-day operations of the school. With all the busyness of the season, both professionally and personally, the mid-year point is one of the most important times of the school year and effective leaders remain diligent about the academic achievement of their students. Here’s a “good list” to help school leaders remain focused during a chaotic time of year!

The holiday season—Thanksgiving through the winter break—provides some unique challenges for school leaders. It is a time when school leaders are busy attending holiday concerts and plays, organizing food and gift drives for needy families, while still responsible for the normal (normal?) day-to-day operations of the school. With all the busyness of the season, both professionally and personally, the mid-year point is one of the most important times of the school year and effective leaders remain diligent about the academic achievement of their students. Here’s a “good list” to help school leaders remain focused during a chaotic time of year!

#1 Revisit Specific School Goals

During the summer months and into the beginning of the school year, school leaders spend valuable time working with stakeholders to identify specific goals for their schools. However, at this time of year, I spend a significant amount of time in schools asking administrators and random teachers what those goals are. Unfortunately, it is uncommon to find someone—administrator or teacher—to speak clearly and in great detail about those goals. Let’s face it, teaching and leading a school is challenging work. As a former turnaround principal, I know this firsthand. It is difficult to stay focused in an environment where anything can, and often does, happen. School leaders who are diligent about keeping their teams focused on their most significant goals have a distinct advantage over those who don’t. The research is pretty clear: Clarity of goals among all stakeholders, including administrators and teachers, is an essential first step to achieving them.

Mid-year is a natural time to revisit these goals and strengthen their clarity among all stakeholders. In assessing this area, I listen closely for administrators and teachers to clearly communicate their measureable goals in the key content areas at the school, department, grade level or content area as well as individual

teacher goals. I have found that when educators speak in terms of numbers of students as opposed to percentages, it makes a significant difference. When educators see percentages they think data; when they convert those percentages into numbers, they see students. Let’s listen in on a teacher leader who understands the power of knowing where her school is going:

Our goal is to receive the highest rating assigned by our state. To achieve this status, our school has to average 62% in each of the nine categories that make up our school rating and we have clear goals in each of these areas. As a math teacher, my department has three  overarching goals: student proficiency (56%), student growth (68%) and student growth with our lowest quartile students (65%). In the area of proficiency, we know that 56% equates to 672 students out of a student body of 1200. Of course we are working so that all students are proficient, however, 672 represents the minimal number of students who must be proficient in math.

overarching goals: student proficiency (56%), student growth (68%) and student growth with our lowest quartile students (65%). In the area of proficiency, we know that 56% equates to 672 students out of a student body of 1200. Of course we are working so that all students are proficient, however, 672 represents the minimal number of students who must be proficient in math.

Now, we have specific goals at the 6th, 7th ad 8th grade levels. I am a seventh grade teacher who teaches six preps a day. Overall, I teach 150 students. 56% of 150 equals 84 students, however, we don’t pro rate our goal like that. Because I am an experienced teacher and two of my sections include advanced students, my target is 70% or a minimum of 105 students. This number allows for me to help compensate for the less experienced teachers on our team who, at this point in time, are still in the early stages of developing their skills.

When listening to this teacher, it was clear to me that she was clear about her school, department, grade level and teacher level goals. Additionally, she was aware of the concepts of individual accountability and team accountability. She clearly knew where the school was headed and u nderstood her department, grade level and personal responsibility to make it happen. If you and your teachers can speak clearly about the direction you are

nderstood her department, grade level and personal responsibility to make it happen. If you and your teachers can speak clearly about the direction you are

headed, you are in a prime position at the mid-point of the year. Of course, knowing where you are headed is only one part of the equation.

#2 Determine Current Status

While understanding the organizational goals answers the “Where are we going?” question, the status component answers the question “Where are we now?” By mid-year, schools have collected enough data to inform them of where they are relative to their most important goals.

While most schools administer large-scale formative assessments that provide big chunks of data, it is the schools who use multiple data points—including attendance and behavior as well as multiple sources of academic performance—and use judicious decision-making to determine specifically which students are on track to accomplish the school goals, that are more successful. Again, let’s hear from the teacher we came across before:

Based on our school-wide data we have determined that if the state calculated our school status today, we would be a little short of our goal. We have gathered data for each component that makes up our status and know which areas are on track and those needing additional attention. Overall, in math, using our data from district-wide form ative assessments, our unit assessments, and teacher judgment, we are pretty much on target as it relates to proficiency with our data showing that 670 students are projected to be proficient. That puts our department two students under our minimum target of 672. In 7th grade, we are a little ahead of our target and my personal data shows that I am five students above my minimum number of 105. Those five students are helping to make up for a deficiency that we have with one of our teachers who continues to struggle with classroom management.

ative assessments, our unit assessments, and teacher judgment, we are pretty much on target as it relates to proficiency with our data showing that 670 students are projected to be proficient. That puts our department two students under our minimum target of 672. In 7th grade, we are a little ahead of our target and my personal data shows that I am five students above my minimum number of 105. Those five students are helping to make up for a deficiency that we have with one of our teachers who continues to struggle with classroom management.

This teacher not only has a clear picture as to where the organization wants to go but is also clear as to where the organization is relative to those goals. Again, she demonstrates her understanding of individual and mutual accountability by recognizing that the team results are more important than her individual results. Understanding the organizational goals and knowing your current status are important steps to accomplishing your goals. However, they only serve as prerequisites to where you ultimately want to go.

#3 Celebrate Growth and Effort

In our constant drive for improvement, we often forget to celebrate the steps along the way. We are fully aware that there are some students who are struggling and we acknowledge that we are struggling to reach them. However, there are many students who we have impacted and we need to take the time to recognize the impact of our efforts and theirs. So, as we celebrate the various holidays, let’s be sure to celebrate the achievements, growth and effort put forth by our students and ourselves. We need to recognize that motivation builds when we receive feedback that reinforces what we are doing that is working, not just the feedback that is designed to redirect our efforts. Let’s see how our teacher is approaching this critical step:

I’ll be the first to tell you that while the data from my personal classes is above my minimum and our department is very near our projections, I am not satisfied with our results. I know we can and will do even better.  However, I have learned to stop and reflect on the progress my students, my team and I have made. I have to think about how far some of my students have come as they continue to put forth the effort to learn the content of 7th grade math. I have to help my team understand and celebrate our collaborative efforts that focused on understanding our standards, asking students to do cognitively complex work, and strengthening our instructional skills. Without each other, we would not be where we are now. I know I am often too hard on myself and tend to focus more on deficits than strengths, but I feel like I have worked harder this year than ever before and it is paying off for my students—our students—and our school.

However, I have learned to stop and reflect on the progress my students, my team and I have made. I have to think about how far some of my students have come as they continue to put forth the effort to learn the content of 7th grade math. I have to help my team understand and celebrate our collaborative efforts that focused on understanding our standards, asking students to do cognitively complex work, and strengthening our instructional skills. Without each other, we would not be where we are now. I know I am often too hard on myself and tend to focus more on deficits than strengths, but I feel like I have worked harder this year than ever before and it is paying off for my students—our students—and our school.

Celebration is often left out of the equation for success. Yet we know that a strong combination of heavy doses of reinforcing feedback mixed in with some redirecting feedback is a strong recipe for success. Mid-year is an important time to recognize our accomplishments, growth and effort.

#4 Create a Short-Term Plan

The final step in the process is to recognize that there are areas that need to be maintained and areas that need attention. I have often said that you can’t accomplish your goals at mid-year but you sure can derail them. Similar to a great basketball or football coach, school leaders help teams to make the necessary adjustments that will allow them to accomplish their goals. It is evident to me that most schools tend to make adjustments that focus on structural changes such as tutoring, Saturday school, small group interventions and the like. More effective leaders  understand that structural interventions are only effective if they are combined with instructional interventions. For instance, Saturday school (structural) is only as effective as the instruction that occurs during that time.

understand that structural interventions are only effective if they are combined with instructional interventions. For instance, Saturday school (structural) is only as effective as the instruction that occurs during that time.

Short-term plans should focus on small steps that can easily be monitored and provide the necessary focus and feedback needed to move toward your most important goals. Let’s hear from our teacher one final time:

We have refined each of our plans relative to the nine components that make up our final school rating. In 7th grade math, we are going to spend more of our team time gaining a deeper understanding of our standards and designing lessons that more closely match the cognitive complexity that our students need to better understand math and that  they will experience when they take their exams. We are also going to continue to develop our skills in implementing cooperative learning techniques that ask students to be more engaged with their learning as opposed to us.

they will experience when they take their exams. We are also going to continue to develop our skills in implementing cooperative learning techniques that ask students to be more engaged with their learning as opposed to us.

We will determine our effectiveness by examining our data at the end of each unit as a team and as individuals. I will also be working with my colleague who is struggling with classroom management in helping her be more consistent in her responses to students’ behaviors.

Once again, this teacher demonstrates a relentless desire to refine and implement a specific plan that is aimed at closing the gap between their goals and their current status. Her team has short-term goals that can be monitored and measured as a way to provide them with the much needed feedback that will allow them to know when they are successful and when they are not. As always, she recognizes her role as a leader in her efforts to help her colleagues.

Summary

Mid-year is a time to ensure that all stakeholders know where they stand relative to the school’s most critical goals and are making the necessary adjustments so that the goals can be met. Because school’s can be chaotic—particularly this time of year—it takes strong leadership from both administrators and teacher leaders to remain diligent in our focus.

Mark Rolewski has assisted schools and school districts in designing and implementing successful turnaround initiatives for over 19 years. Mark has assisted with school turnaround in many districts and schools including those in Florida, New York City, Hartford, New Orleans, Memphis, Kansas City and Los Angeles. He is widely sought after by schools and school districts to speak about and assist with turnaround initiatives.

Mark Rolewski has assisted schools and school districts in designing and implementing successful turnaround initiatives for over 19 years. Mark has assisted with school turnaround in many districts and schools including those in Florida, New York City, Hartford, New Orleans, Memphis, Kansas City and Los Angeles. He is widely sought after by schools and school districts to speak about and assist with turnaround initiatives.

For additional information, please visit Mark’s webpage.

Click here if you would like to sign up to receive future articles via email. Thank you.

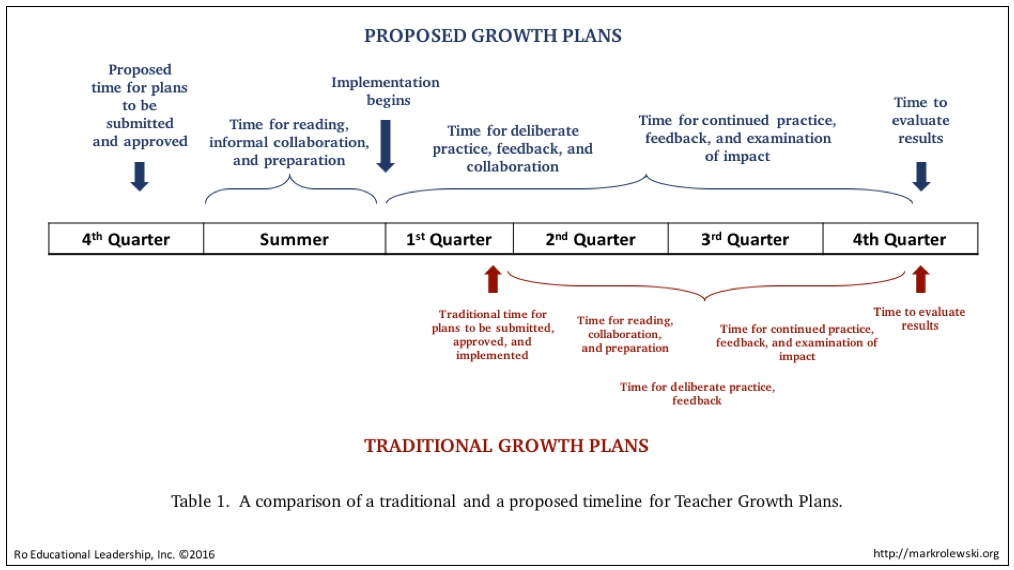

At this time of year, teachers across America are designing and submitting for approval their Professional Growth Plans as part of the evaluation process. This annual ritual asks teachers to identify and develop a plan of action outlining an area of instructional growth. While this activity is well intentioned, it is my observation that these plans are largely ineffective, completed primarily to comply with state and district requirements, and—most importantly—they take away valuable time necessary to truly improve instruction in schools.

At this time of year, teachers across America are designing and submitting for approval their Professional Growth Plans as part of the evaluation process. This annual ritual asks teachers to identify and develop a plan of action outlining an area of instructional growth. While this activity is well intentioned, it is my observation that these plans are largely ineffective, completed primarily to comply with state and district requirements, and—most importantly—they take away valuable time necessary to truly improve instruction in schools. ing, teachers dust off their plans and begin the process of trying to document that they have completed their plan and frantically assemble the requisite documentation that will eventually lead to meeting the requirements of the plan. The results of the plans are submitted to the appropriate administrator who, in nearly all cases, provides the stamp of approval indicating that the requirements have been met.From an administrative standpoint, multiply this by the typically large number of teachers an administrator evaluates and you begin to understand the massive amount of time it takes to complete an activity that yields very little return on investment. Teachers and school leaders—especially in turnaround schools—have little time to engage in time-consuming activities that take away from true school improvement

ing, teachers dust off their plans and begin the process of trying to document that they have completed their plan and frantically assemble the requisite documentation that will eventually lead to meeting the requirements of the plan. The results of the plans are submitted to the appropriate administrator who, in nearly all cases, provides the stamp of approval indicating that the requirements have been met.From an administrative standpoint, multiply this by the typically large number of teachers an administrator evaluates and you begin to understand the massive amount of time it takes to complete an activity that yields very little return on investment. Teachers and school leaders—especially in turnaround schools—have little time to engage in time-consuming activities that take away from true school improvement

Furthermore, learning a new skill can be uncomfortable. Neurologically speaking, we are much more comfortable relying on the skills that have become habits as opposed to learning something new. Learning a new skill requires that we use the part of our brain that causes us to slow things down—or be deliberate—so our brain’s can learn the new behaviors. Over time, we learn to be less deliberate and more comfortable with our new skill. As we become more and more skilled we have to continue to receive feedback that will allow us to perform at an even higher level. Too often, after the first wave of discomfort is gone we think that we are now skilled. Understand that there is skill and then there is “skillful enough to impact student achievement.” Becoming highly skilled requires learning a skill and then being comfortable with the discomfort of learning it at a higher level. This cycle needs to be repeated in an ongoing manner to reach the level necessary to make a professional growth plan worth the effort.

Furthermore, learning a new skill can be uncomfortable. Neurologically speaking, we are much more comfortable relying on the skills that have become habits as opposed to learning something new. Learning a new skill requires that we use the part of our brain that causes us to slow things down—or be deliberate—so our brain’s can learn the new behaviors. Over time, we learn to be less deliberate and more comfortable with our new skill. As we become more and more skilled we have to continue to receive feedback that will allow us to perform at an even higher level. Too often, after the first wave of discomfort is gone we think that we are now skilled. Understand that there is skill and then there is “skillful enough to impact student achievement.” Becoming highly skilled requires learning a skill and then being comfortable with the discomfort of learning it at a higher level. This cycle needs to be repeated in an ongoing manner to reach the level necessary to make a professional growth plan worth the effort. nnual professional growth plans as outlined in most districts’ teacher evaluation process often have a large impact on time but little return on investment

nnual professional growth plans as outlined in most districts’ teacher evaluation process often have a large impact on time but little return on investment

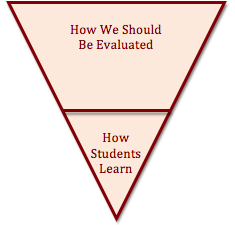

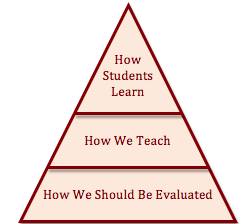

chools introduce multiple sets of criteria when observing and providing feedback to teachers and schools. For example, one set exists for teacher evaluation while other sets are used for district walkthroughs, state walkthroughs, turnaround schools, and yet

chools introduce multiple sets of criteria when observing and providing feedback to teachers and schools. For example, one set exists for teacher evaluation while other sets are used for district walkthroughs, state walkthroughs, turnaround schools, and yet liability—between school administrators in their observations and ratings of teachers. While this is an important undertaking, I believe that the most important inter-rater reliability is between teachers and administrators who share a common understanding of the evaluation criteria.

liability—between school administrators in their observations and ratings of teachers. While this is an important undertaking, I believe that the most important inter-rater reliability is between teachers and administrators who share a common understanding of the evaluation criteria. between those evaluating and those being evaluated, it is often a recipe for conflict that is rooted in each person’s individual interpretation of the

between those evaluating and those being evaluated, it is often a recipe for conflict that is rooted in each person’s individual interpretation of the

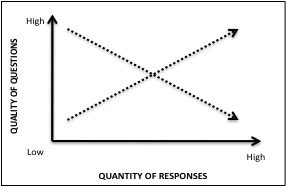

cooperative learning strategies all tend to “ask” more—or all—students to respond which results in more “gets.” These are what I call the “Equal Opportunity Teachers” because they have the skills to provide equal opportunities for all students to be engaged.

cooperative learning strategies all tend to “ask” more—or all—students to respond which results in more “gets.” These are what I call the “Equal Opportunity Teachers” because they have the skills to provide equal opportunities for all students to be engaged.

less about increasing achievement, they do just that.

less about increasing achievement, they do just that.

Too often, blaming and complaining absolves individuals of the responsibility to change. Don’t get me wrong—I understand blaming and complaining. It clearly is the easiest thing to do when things are not going your way. And, as we all know, much in a turnaround school related to student behavior and student learning does not go the way we intend it to.

Too often, blaming and complaining absolves individuals of the responsibility to change. Don’t get me wrong—I understand blaming and complaining. It clearly is the easiest thing to do when things are not going your way. And, as we all know, much in a turnaround school related to student behavior and student learning does not go the way we intend it to.

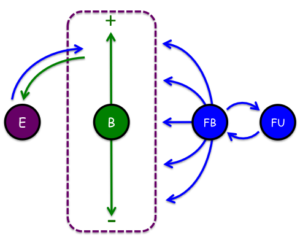

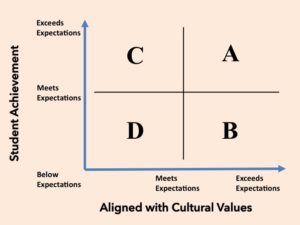

The next category of teacher falls in the “B” quadrant. While “B” teachers do not yet have the skills to influence student achievement in a significant way, they have tremendous heart and drive. They want to align their behaviors with the expectation of the organization and are highly ‘coachable.” It is incumbent on school leaders to have strong, systemic processes for developing teachers that include many avenues for high quality, frequent feedback so that the rate of improvement is high. School leaders—including “A” teachers—should devote significant amounts of time to developing their “B” teachers by providing support in improving instruction and professional behaviors as well as providing the emotional support necessary to remain diligent in the learning process. With deliberate practice, quality feedback, mentorship, and time, “B” teachers can develop into “A” teachers.

The next category of teacher falls in the “B” quadrant. While “B” teachers do not yet have the skills to influence student achievement in a significant way, they have tremendous heart and drive. They want to align their behaviors with the expectation of the organization and are highly ‘coachable.” It is incumbent on school leaders to have strong, systemic processes for developing teachers that include many avenues for high quality, frequent feedback so that the rate of improvement is high. School leaders—including “A” teachers—should devote significant amounts of time to developing their “B” teachers by providing support in improving instruction and professional behaviors as well as providing the emotional support necessary to remain diligent in the learning process. With deliberate practice, quality feedback, mentorship, and time, “B” teachers can develop into “A” teachers.