Listen with curiosity, speak with honesty, act with integrity.

Roy T. Bennett, The Light in the Heart

Democratic freedom comes at a great cost. It is not an ideal that can just be demanded by individuals, but rather must be collectively earned. Therefore, our success as a nation is contingent upon our willingness and ability to govern ourselves— both individually and collectively. Only through these efforts can we navigate our way to a new and better tomorrow, and many tomorrows after that.

Many great thinkers and leaders have linked freedom to self-governance. Greek philosopher Plato linked freedom to one’s ability to govern himself. Seventeenth century English philosopher and key influencer of the framers of the US Constitution, John Locke, claimed that while men were naturally free, they had to transfer some of their rights to a government established by the consent of the people in order to pursue life, liberty and property. Self-governance is the price we must be willing to pay to be free.

But the process of self-governance is as fragile as it is strong. If we take it for granted, it fails, if we nurture it, it flourishes. Our Founding Fathers believed that to be sustained, self-governance required an educated populace. Thomas Jefferson believed that “self-government is not possible unless the citizens are educated sufficiently” and advocated that “sustainable education” be provided for all citizens.

Later, Abraham Lincoln stated that education was “the most important subject which we as a people can be engaged in” to support the American democracy. Franklin D. Roosevelt wrote that “Democracy cannot succeed unless those who express their choice are prepared to choose wisely. The real safeguard of democracy, therefore, is education.”

Education is “the most important subject which we as a people can be engaged in” to support the American democracy.

~Abraham Lincoln, March 9, 1832

Simply put, freedom is not possible without self-governance and self-governance is not sustainable without education.

Formal K-12 education in the United States prepares its citizens to participate in our democracy in many ways. One way is to provide strong foundational knowledge that includes understanding various forms of government, learning the lessons of our history and the histories of others, comprehending our guiding documents such as the Constitution and Bill of Rights, and understanding liberty, politics, the rule of law and the value of voting. This foundation provides the critical knowledge base that every citizen should possess and continue to study.

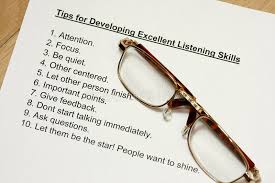

However, knowledge is not enough. Self-governance requires not just understanding, but action. Therefore, schools emphasize two fundamental skills, interwoven into one, to form the basis for participation in a democracy and securing our freedoms—speaking and listening. For when we do them well, we truly fulfill our patriotic duty. When we do them poorly, we erode our freedom.

Let’s examine how schools guide our students toward participating in our democracy with a particular emphasis on those two specific bedrock skills. Maybe, along the way, it will serve as a reminder for all of us interested in sustaining our freedoms.

Educators understand that what is taught in schools is determined by each state individually through a series of published standards. Standards determine what is taught in numerous content areas including mathematics, art, science and language arts. While many standards address the skills necessary to participate in self-governance, let’s focus on one standard in particular. This standard extends from kindergarten through graduation, gradually increasing in complexity as students progress through their schooling. Regardless of grade level, the premise remains the same:

Students should be able to initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions with diverse partners on grade appropriate topics, texts, and issues, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

Simply stated, the first part of this standard focuses on teaching students to listen and speak to people who are different from themselves. “Diverse partners” has many connotations in today’s world and is constantly changing but includes people from different countries of origin, cultures, languages, religions, ages, sexual preferences and political persuasions. Diversity is this country’s greatest strength—and yet our greatest weakness. We are at our best when we are united and at our worst when we are divided.

United, of course, doesn’t mean we have to agree on everything. Quite the contrary. We know that, if done well, discourse allows us to move toward a more perfect union for all of our citizens, as put forth in the Preamble of the United States Constitution. It not only allows for others to be heard but allows us to refine our own beliefs and gain a clearer understanding of the beliefs of others. It provides us with the opportunity to respect each other’s point of view and even change our minds. It provides the opportunity to learn tolerance and to seek common ground. Speaking and listening, together, form part of the foundation of a stronger Union.

To help children—and all citizens—to “participate effectively” in discussions with diverse people, our speaking and listening standard includes some guiding principles. One such guideline states:

Work with peers to set rules for collegial discussions and decision-making (e.g., informal consensus, taking votes on key issues, presentation of alternate views), clear goals and deadlines, and individual roles as needed.

This guideline focuses on the rules necessary to ensure that all people can be heard and can make effective decisions. When asked, even young students can list rules such as listen to each other, don’t interrupt, take turns, and stop when the teacher tells you to stop. Indeed, the best teachers include students in creating rules for engagement, provide opportunities for students to deliberately practice these skills, and interweave speaking and listening with all content areas.

As early as fourth grade, the following caveat is added:

Come to discussions prepared, having read and researched material under study; explicitly draw on that preparation by referring to evidence from texts and other research on the topic or issue to stimulate a thoughtful, well-reasoned exchange of ideas.

This guideline focuses on the ability of students—all citizens—to engage in an “exchange of ideas” that is based on reasoning or logic. Indeed, teaching students to provide accurate evidence to support their beliefs with reasoning or logic is a great challenge for schools. However, one attribute of a quality teacher, regardless of the content area they teach, is the ability to weave reasoning and logic into their teaching by constantly asking the questions Why? and Can you justify that?

These questions require effort on behalf of students and require them to think beyond their own personal experiences and opinions. The difficulty of teaching reasoning or logic is compounded by the cacophony of opinions or positions that are supported with the weak or twisted evidence available on various news channels (where entertainment is disguised as news) and social media platforms. Even our foreign adversaries recognize that their best strategy for weakening or defeating our democracy is to cleverly infiltrate our social media in an attempt to pit us against one another.

Students must recognize the differences between news, opinion, and propaganda. They must also guard against their own bias by not exposing ourselves only to information that matches their beliefs but instead recognize the value of multiple sources of information. Media literacy must be emphasized including using resources that subscribe to the Society of Professional Journalists’ code of ethics. Remember: speaking and listening, when done well, make our country great. When done poorly, they erode our freedom.

When students don’t possess the skills to discern evidence from hype, they become susceptible to making errors in their reasoning (i.e., overgeneralizing, relying on hearsay, counterfactual thinking, and catastrophizing), or they simply resort to ad hominem (i.e. personal attacks).

Furthermore, we must understand the danger in the fallacies that are encouraged when complex concepts are reduced to three-letter phrases or acronyms (i.e., Black Lives Matter, Blue Lives Matter, All Lives Matter), memes, or by asking questions that encourage only dichotomous thinking (i.e. either/or). Collective self-governance consists of complex ideas that require a well-reasoned exchange of ideas as opposed to explosive reactions. Our ability to engage in a thoughtful, rational discussion requires that we closely monitor and evaluate our information intake.

But education is not just the responsibility of the schools, it is the responsibility of each of our citizens. We must embrace the idea that freedom is embedded in the behaviors of each and every one of us. Therefore, it is incumbent upon each of us to regulate—or govern—ourselves. We must be disciplined enough to consistently model the behaviors (i.e., honesty, open-mindedness, tolerance) expected of a member of an educated populace. We must be willing to do what we ask our students to do—engage in the types of behaviors that make us stronger, not tear us apart.

Freedom is contingent upon self-government and self-government is dependent on its citizens engaging in a well-reasoned exchange of ideas. This is one of our most important civic duties. Effective listening and speaking are at the foundation of this process. They make us stronger—individually and collectively—and contribute to sustaining the freedom we cherish so dearly.

For additional information, please visit Mark’s webpage.

Click here if you would like to sign up to receive future articles via email. Thank you.

Mark Rolewski has assisted schools and school districts in designing and implementing successful turnaround initiatives for over 20 years. Mark has assisted with school turnaround in many districts and schools including those in Florida, New York City, Hartford, New Orleans, Memphis, Kansas City and Los Angeles. He is widely sought after by schools and school districts to speak about and assist with turnaround initiatives.