Making Teacher Evaluation Meaningful

The process of school turnaround requires an extreme focus on the things that matter most to student learning. Paramount to this is hiring quality people who develop strong relationships with students, collaborate to set and monitor goals, hold each other mutually accountable for results, and relentlessly pursue multiple avenues in an attempt to reach all students. However, while turnaround schools are busy fostering this type of culture, there are certain activities that take valuable time away from the things that matter most.

This article addresses an area of schooling that requires a significant amount of time—particularly on the part of administrators—but often yields very little return on investment in teaching quality or student achievement. I am referring to the typical teacher evaluation process.

The Typical Teacher Evaluation Process

Administrator Standpoint

First, let’s think of the time spent. The school year usually begins with an in-service designed to introduce or update administrators on the criteria and processes that will be used to evaluate teacher performance. Administrators, in turn, share this information with teachers during pre-school activities and, in many cases, throughout the year. Then comes the scheduling of the various teachers—new teachers, teachers with under three years of experience, veteran teachers, teachers who are on improvement plans—all designed to ensure that each teacher receives the appropriate number of evaluations necessary to meet each district’s requirements. Next come the pre-conferences followed by observations, post-conferences, and the time it takes to document everything and upload it into a district’s evaluation system. Multiply this by the usually large number of teachers an administrator has to evaluate and you begin to realize that simply completing all the evaluations can absorb a significant amount of administrator time. This workload often causes the teacher evaluation process to be more one of compliance than one of meaning.

Teacher Standpoint

Next, let’s look at it from a teacher standpoint. First, teachers are busy people. They spend most of their time in front of students with very little time left to collaborate, to plan and reflect on the effectiveness of their practice, or to engage in high quality professional development with follow-up regarding teaching techniques. Teacher evaluation is often viewed more as an event as opposed to a process woven into the day-to-day fabric of school improvement.

Now, I am not advocating for the elimination of the teacher evaluation process. Quite the contrary. In my experience, nearly all administrators that I have worked with over the years truly want to make the evaluation process a valuable one for their teachers. Conversely, teachers want to know that they are doing a good job and are open to feedback that they believe is valid. I believe that we can significantly increase the power of teacher evaluation if we begin to take a few steps toward making it a meaningful experience for all and worthy of the time it requires.

Let’s first examine some barriers that keep the current process flawed.

Barrier #1: The Cart Before the Horse

In most organizations, they first determine clear outcomes and then identify a set of behaviors that will most likely lead to their accomplishment while supporting the values of the organization. Then, some type of appraisal instrument is designed to communicate to the employees what behaviors are expected, and regular reviews are conducted to let employees know where they stand relative to the organizational expectations.

Often in education, we begin with the evaluation tool. Indeed, many teacher evaluation tools that are being used today were hastily adopted by states and local school districts as a result of the Obama administration’s Race to the Top (RTT) educational initiative so that states could compete for substantial federal funding. This led to districts adopting frameworks that were externally designed (e.g., Danielson, Marzano) or assembled by states or local districts. While many of these instruments—particularly those that were externally designed—include valid criteria for evaluating teacher performance, the question is: Were they adopted or designed with the intent of securing an evaluation tool or do they truly represent the expectations of quality teaching of the school system in which they are being used?

I contend that they were adopted primarily to secure an evaluation tool. To support this belief, I have repeatedly seen states, districts and s chools introduce multiple sets of criteria when observing and providing feedback to teachers and schools. For example, one set exists for teacher evaluation while other sets are used for district walkthroughs, state walkthroughs, turnaround schools, and yet

chools introduce multiple sets of criteria when observing and providing feedback to teachers and schools. For example, one set exists for teacher evaluation while other sets are used for district walkthroughs, state walkthroughs, turnaround schools, and yet

another set when external programs are adopted. Principals and teachers often tell me that “different observers look for different things.”

When there is no consensus on what quality teaching is, these multiple sets of criteria clash with one another and serve to further confuse teachers and administrators and dilute a common understanding of the criteria for evaluating effective teaching. Simply put, many evaluation tools serve as just that—evaluation tools—and do not represent a consensus of what quality teaching should be in a school system. When multiple sets of criteria exist using different language to communicate similar techniques, it becomes more difficult for teachers and administrators to harness the instructional focus that is necessary for school turnaround and to engage in meaningful dialogue about quality instruction.

The reality is that most teachers and administrators have their own ideas about what constitutes quality teaching. These ideas are developed over time based mostly on personal experience, trial and error in the classroom, and the individual efforts to learn about quality teaching. When a district adopts an instrument without acknowledging this schema, it leads to a chasm between what people believe is quality teaching and what the adopted instrument states. Unless this chasm is addressed, teachers often treat the evaluation process as a necessary event in which they must comply.

Barrier #2: Emphasis on Administrator Inter-rater Reliability

In baseball, players and fans alike expect consistency between the various umpires that call balls and strikes. Similarly, in schools, teachers and central office administrators expect consistency—or, inter-rater re liability—between school administrators in their observations and ratings of teachers. While this is an important undertaking, I believe that the most important inter-rater reliability is between teachers and administrators who share a common understanding of the evaluation criteria.

liability—between school administrators in their observations and ratings of teachers. While this is an important undertaking, I believe that the most important inter-rater reliability is between teachers and administrators who share a common understanding of the evaluation criteria.

Too often, administrators receive many more hours of training in the system than do teachers, creating an environment where the people being evaluated know less about the criteria than the people conducting the evaluations. When there are inconsistencies  between those evaluating and those being evaluated, it is often a recipe for conflict that is rooted in each person’s individual interpretation of the

between those evaluating and those being evaluated, it is often a recipe for conflict that is rooted in each person’s individual interpretation of the

criteria as opposed to sharing a common understanding of what quality teaching looks like.

Barrier #3: Valid Teaching Techniques Introduced through Evaluation

Possibly one of the worst ways to introduce teachers and administrators to effective teaching practices is to do it through an evaluation system. Yet, this seems to be the most prevalent way in which it occurs. Unfortunately, the term evaluation tends to be associated with judgment and not with learning. This is perpetuated through administrator training that often focuses more on ratings and less on understanding what quality instruction looks like, the research on which it is based, why it is effective and how to influence the quality of instruction among teachers of various skill levels.

Teachers tend to get most of their information about the appraisal system from their administrators so if administrator training is primarily focused on ratings, that is the information that teachers receive. This approach encourages many teachers and administrators to focus more on the ratings, and less on the actual criteria or understanding of quality instruction. Furthermore, teachers tend to view the evaluation process as an event and not part of the overall system for improving instruction.

Some Considerations

If teacher evaluation is ever going to be an integral part of the overall process of improving instruction, it must be woven into a systematic process designed to improve instruction and increase achievement and not just be addressed in isolation.

What is learning?

The most success I have in working with teacher evaluation systems never begins with the evaluation tool itself; instead, it begins with an understanding of learning. I frequently ask, “What is learning?” and emphasize that effective teaching should first and foremost align with how people learn and not with an evaluation tool. Specific information about how the neurological system works to gather, process, store and retrieve information leads to an understanding of why certain teaching techniques are effective.

For example, as opposed to telling teachers that they are expected to use cooperative learning because it is part of the evaluation instrument, I emphasize that cooperative learning is one of the best ways students can support one another’s learning in gathering, processing, storing and retrieving information. Quality training in any teaching technique always includes the “why” and not just the “how.”

Effective teaching aligns with how students learn.

The bottom line is that most teachers don’t want to be told how to teach nor do they value the content of evaluation instruments that don’t help them improve their teaching and their students’ learning. Ongoing dialogue between how people learn and how one’s teaching should align with the learning process is central to setting the foundation for what effective teaching is. Ultimately, effective teaching should align with how people learn and teachers who understand this also understand the importance of being held accountable for teaching in that manner.

Aligning the System

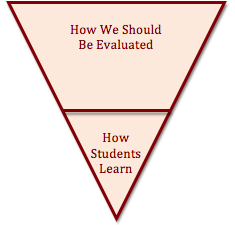

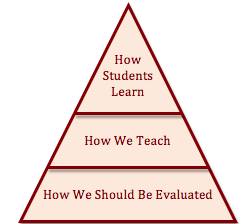

The following illustration represents the current system that aligns how we should teach to an evaluation system.

When we invert the triangle, we begin with how students learn and then align our teaching to that and ultimately hold teachers accountable for teaching in that manner.

When presented in this manner, teachers are much more willing to engage in the necessary dialogue that allows for a common understanding of the language included in the instrument. Furthermore, when the common understanding exists, there is less focus on ratings because the most important inter-rater reliability is when teachers and administrators share a common understanding of the criteria that will be used in evaluating quality teaching and affecting student learning.

Once a common language is adopted and the ongoing process of deepening the knowledge of its content begins, district and school leaders must be diligent in ensuring that other criteria do not supersede the common language adopted by the district or school. Instead of using multiple criteria for different situations, leaders must serve as “air traffic control” to avoid different sets of criteria clashing with one another. Teachers and administrators must be clear on “how we teach here” and the language we use to communicate. If additional criteria are to be used, they should be integrated into the common system and not be permitted to operate in isolation.

Summary

Since we know that the quality of instruction is the major determinant in student achievement, it is imperative that school systems identify and promote a common understanding of a common set of criteria of what constitutes quality instruction. While this is true of all schools, it is particularly true of turnaround schools. Emphasis should not solely be on the inter-rater reliability of administrator ratings but on the consistency by which teachers and administrators view the criteria used in evaluation. Furthermore, district and school leaders must be cautious of multiple sets of criteria used to support schools. As we know, turnaround schools have increased monitoring and multiple interventions operating simultaneously. Teachers and administrators can remain more diligent in focusing on what’s important when there is one set of criteria that defines quality teaching in a school and when that criteria is based on how students learn. While evaluation has an important role in turnaround schools, focusing on what matters most will help us stop wasting our time on things that don’t cause instruction to improve and make the process more meaningful for everyone.

Mark Rolewski has assisted schools and school districts in designing and implementing successful turnaround initiatives for over 19 years. Mark has assisted with school turnaround in many districts and schools including those in Florida, New York City, Hartford, New Orleans, Memphis, Kansas City and Los Angeles. He is widely sought after by schools and school districts to speak about and assist with turnaround initiatives. This is the seventh installment of an ongoing series that outlines many of the components of a turnaround initiative.

For additional information, please visit Mark’s webpage.

Click here if you would like to sign up to receive future articles via email. Thank you.

How I wish our focus could be on teaching and learning for students, teachers, administrators and district leaders. When learning takes a backseat to initiatives and programs, no one wins.

I couldn’t agree with you more, Maggie. Leaders are learners! That’s one of the reason you are such a great leader. It was my pleasure to work with you for so many years. Here is a summary of the resrearch on quality professional develoment by Timperley et al (2007). It is true for teachers and leaders.

*Occurs over a long period of time (three to five years)

*Involves external experts

*Leaders/Teachers are deeply engaged

*It challenges leaders’/teachers’ existing beliefs

*Leaders/Teachers talk to each other about teaching

*District and school leadership supports leaders’ and teachers’ opportunities to learn and provides opportunities within the school structures or district structures for this to happen

(http://www.oecd.org/edu/school/48727127.pdf)

Let’s not forget, that leaders can only lead to the level they know how to lead! If leaders (teacher leaders and administrators) are not continuously learning, then they will not continue to move schools forward to benefit the students.